Volume 19, Issue 6 (Nov-Dec 2025)

mljgoums 2025, 19(6): 5-8 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Prabhu K, Theresa Dsouza R, Devadiga S, Antony B, Dias M. Identification of Candida species isolated from clinical samples by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis. mljgoums 2025; 19 (6) :5-8

URL: http://mlj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1796-en.html

URL: http://mlj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1796-en.html

1- Department of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India

2- Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India

3- Department of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India; Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India

4- Department of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India; Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India ,beenafmmc@gmail.com

2- Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India

3- Department of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India; Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India

4- Department of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College, Mangalore, India; Father Muller Research Centre, Mangalore, India ,

Full-Text [PDF 462 kb]

(654 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1527 Views)

Discussion

Prompt and accurate identification of yeast is critical for effective patient management in any infectious process. Furthermore, the rising prevalence of NAC species can complicate the selection of appropriate antifungal therapy (3-6).

Infections caused by NAC species are clinically indistinguishable from those caused by C. albicans; however, antifungal resistance is more frequently associated with NAC species (1). Our current research demonstrated a predominance of NAC, accounting for 72.84% of the isolates responsible for various clinical candidiasis conditions. This finding aligns with a study conducted by Umamaheshwari et al. in Southern India, which reported that 73.64% of candidiasis cases were attributable to NAC species (5). Furthermore, the emergence and predominance of NAC in various body fluids have also been highlighted by Singh DP et al. (12).

In the current study, C. tropicalis (30.40%) was determined to be the most frequently isolated species. The finding of our study aligned with the results reported by Gautam et al. (26.72%) and Anita et al. (37.09%) for the isolation frequency of C. tropicalis (13,14). While traditional phenotypic identification methods, which rely on biochemical reactions, are cost-effective, they are inherently time-consuming. Conversely, techniques involving nucleic acid detection, although highly specific, are often expensive. Consequently, MALDI-TOF MS has emerged as a novel and efficient method for the identification and speciation of yeasts, such as Candida (9,11). MALDI-TOF MS was utilized for accurate species-level identification of Candida isolates. The on-plate extraction method simplified the procedure, and the technique demonstrated high throughput and cost-effectiveness. Specifically, its ability to analyze 96 isolates per run using inexpensive reagents makes it significantly more economical than traditional biochemical or nucleic acid-based methods. MALDI-TOF MS successfully identified all suspected Candida species. A high degree of confidence was achieved for 91.81% (314/342) of the isolates, with log scores > 1.7, which is consistent with findings reported by Periera et al. (10).

The multidrug-resistant yeast C. auris is frequently misidentified by conventional phenotypic automated systems as other Candida species, including Candida haemulonii (C. haemulonii), Candida famata (C. famata), Candida sake (C. sake), and Candida lusitanie (C. lusitaniae). Definitive confirmation of C. auris requires advanced methods, MALDI-TOF MS or DNA sequencing (15). In this study, a concerningly high prevalence of C. auris (11.69%) was observed, particularly among burn patients. These patients are highly susceptible to acquiring C. auris infections from the hospital environment due to their impaired immune defense and extensive wounds (16). This observed dominance of C. auris is consistent with findings from a previous study conducted in western India by Prayag PS (6).

Accurate and timely diagnosis of NAC is crucial for the selection of appropriate empirical antifungal treatment. Furthermore, the implementation of stringent infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols is essential for patients colonized or infected with C. auris to effectively contain this multidrug-resistant yeast and mitigate the risk of institutional outbreaks.

Conclusion

The role of Candida species, encompassing NAC and novel drug-resistant strains, necessitates a cautious approach in clinical and laboratory settings. MALDI-TOF MS offers a viable alternative to conventional and automated identification systems that rely on biochemical reactions for Candida speciation. Despite the significant initial capital investment, the use of less expensive reagents and the implementation of simplified protocols establish MALDI-TOF MS as a cost-effective method for the routine identification of yeast isolates from clinical specimens.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the faculty and technical staff of the Department of Microbiology for their valuable assistance.

Funding sources

This study did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Ethical statement

Reference No. FMIEC/CCM/550/2023 (Protocol No. 512/2023)

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author contributions

K.P.: Study concept, Study design, Data analysis, and Manuscript writing and Review; R.T.P.: Data collection and Manuscript writing; S.D. and B.A.: Data analysis and Manuscript review; M.D.: Manuscript review.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the corresponding author to any interested party upon presentation of a reasonable request.

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Introduction

Candida species are prevalent organisms commonly found colonizing the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and skin (1). These fungi are capable of causing substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients who have compromised epithelial barriers and underlying impairments in their immune defense mechanisms (2). The genus Candida is a type of yeast that encompasses over 150 different species. Among these, a limited number are frequently recognized as pathogenic, including Candida albicans (C. albicans), Candida tropicalis (C. tropicalis), Candida parapsilosis (C. parapsilosis), and Candida glabrata (C. glabrata) (1). Candidiasis frequently occurs in individuals who are immunocompromised, such as patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and following extensive medical interventions, including prolonged antibiotic therapy, invasive surgery, use of indwelling intravenous catheters or prosthetic devices, administration of hyperalimentation fluids, or chemotherapy. Candida species are responsible for a range of mucosal and cutaneous infections, which include oral candidiasis, esophagitis, gastrointestinal candidiasis, cutaneous candidiasis, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Furthermore, Candida can lead to more critical systemic infections, with invasive bloodstream infections being the most prevalent and clinically significant among them (1).

Reports from numerous countries worldwide indicate an alteration in the epidemiology of Candida infections, marked by a gradual transition from the dominant species, C. albicans, to a prevalence of non-albicans Candida (NAC) species, including C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and Candida krusei (C. krusei) (2-5). Given that both pathogenicity and appropriate therapeutic approaches vary by species, accurate species identification is crucial (1). The recovery of these NAC organisms from diverse hospital settings and on the hands of healthcare personnel suggests nosocomial transmission. Noteworthy among these NAC species is Candida auris (C. auris), a recently recognized, multidrug-resistant yeast that has been responsible for outbreaks across several geographic regions. To implement stringent infection control measures within a hospital setting, rapid and accurate identification of C. auris is crucial (6).

The laboratory diagnosis of Candida is generally straightforward due to the microscopic presence of yeast forms and pseudo-hyphae. These organisms exhibit robust growth on standard culture media and in blood culture bottles, eliminating the need for specialized culturing ingredients. Conventional phenotypic assays, such as the rapid, presumptive germ tube test and chlamydospore formation, are employed to distinguish C. albicans from NAC species. However, these methods are incapable of providing further species-level differentiation among NAC isolates and are subject to inherent limitations of false positive and false negative results. Other phenotypic identification methods, which rely on biochemical reactions, include systems like the Analytical Profile Index (API), VITEK, and PHOENIX. However, these methods typically require 18-24 hours to yield identification results (1). Conversely, molecular approaches such as those based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing offer high accuracy but are often associated with significant processing time and considerable expense (7).

A novel approach employing matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) offers a rapid and highly accurate method for identifying yeasts directly from culture plates based on their unique protein profile, typically within 20 minutes (8,9). This technique was utilized in the current study, which was executed at a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, with the objective of identifying Candida species that were isolated from various clinical specimens through MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Methods

Study setting and design

This research, structured as a retrospective, laboratory-based study, utilized data procured from the Department of Microbiology at Father Muller Medical College Hospital in Mangalore, Karnataka, India, from September 2022 to November 2023. The study's cohort comprised all clinically significant Candida isolates that were successfully recovered from routine clinical specimens during the specified timeframe.

Specimen collection and processing

Blood samples were obtained and inoculated into BacT/ALERT aerobic culture bottles (bioMérieux, France). These bottles were subsequently incubated at a temperature of 37°C for a maximum duration of 5 days. Any bottles indicating a positive signal for yeast proliferation were subjected to Gram staining, followed by subculturing onto both blood agar and Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDA) media (Both supplied by HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India).

All remaining clinical samples, encompassing high vaginal swabs, urine, pus, central venous catheter (CVC) tips, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, nail clippings, ascitic fluid, wound swabs, tissue, bile, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), underwent processing in accordance with standard microbiological protocols. These specimens were inoculated onto suitable culture media and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 24–48 hours.

Specimens specifically requested for fungal culture were inoculated onto two separate slopes of SDA supplemented with gentamicin (Omitting cycloheximide). These cultures were then incubated at 25°C and 37°C for a maximum duration of four weeks. Direct examination of all specimens was conducted utilizing Gram stain and/or 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mounts for the primary purpose of detecting yeast cells.

Isolation and preliminary identification

Following an incubation period of 24–48 hours, culture plates exhibiting smooth, cream-to-white, and glabrous colonies-morphologically indicative of Candida species-were chosen for further analysis. A Gram stain was subsequently performed on these colonies to confirm the characteristic yeast morphology. These presumptive isolates were then subcultured onto HiChrome™ Candida Differential Agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) for a reliable, phenotypic differentiation based on colony color.

Species identification by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)

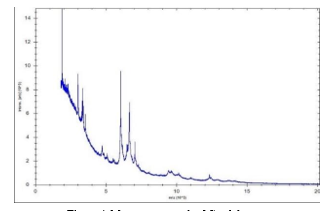

Species-level identification was definitively achieved utilizing the Bruker Microflex LT/SH MALDI-TOF MS system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in conjunction with MALDI Biotyper software (MBT Compass version 12.0.0.0_10833). This system operates by comparing the distinctive ribosomal protein spectra of the isolates against a specialized reference database for organism identification (10).

Sample preparation (Extended direct transfer method)

A pure colony was thinly smeared onto a polished steel MALDI target plate. Subsequently, 1 μL of a 70% formic acid solution was applied to the sample and permitted to air-dry at room temperature. Following this step, 1 μL of the α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) matrix solution was added and allowed to completely dry.

Data acquisition and interpretation

The MALDI Biotyper software was utilized in automatic mode to acquire the spectra. Interpretation of the resulting identification scores adhered to the manufacturer's established criteria: A score of ≥ 2.0 signified a high-confidence identification at the species level; scores ranging from 1.7 to 1.99 indicated genus-level identification with lower confidence; and scores of < 1.7 were classified as unreliable. The C. albicans ATCC 90028 functioned as the positive control, while spots containing matrix only were employed as the negative control (11).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data (Such as specimen type, species distribution, and demographic information) were presented using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables (e.g., patient age) were summarized by the median accompanied by the interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel were employed for data analysis.

Results

A comprehensive analysis was conducted on 342 Candida isolates derived from clinical specimens over a 15-month period, spanning from September 2022 to November 2023. The median age of patients at the time of infection was 46.5 years, with a notable male predominance. The primary source of the isolates was blood (136/342, 39.76%) (Table 1). NAC species constituted the majority (254/342, 72.84%), outnumbering C. albicans. Among the NAC group, C. tropicalis was the most prevalent isolate (30.40%), followed by C. parapsilosis (14.32%). Furthermore, 40 strains of C. auris were identified during the study (11.69%) (Table 2).

Candida species are prevalent organisms commonly found colonizing the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and skin (1). These fungi are capable of causing substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients who have compromised epithelial barriers and underlying impairments in their immune defense mechanisms (2). The genus Candida is a type of yeast that encompasses over 150 different species. Among these, a limited number are frequently recognized as pathogenic, including Candida albicans (C. albicans), Candida tropicalis (C. tropicalis), Candida parapsilosis (C. parapsilosis), and Candida glabrata (C. glabrata) (1). Candidiasis frequently occurs in individuals who are immunocompromised, such as patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and following extensive medical interventions, including prolonged antibiotic therapy, invasive surgery, use of indwelling intravenous catheters or prosthetic devices, administration of hyperalimentation fluids, or chemotherapy. Candida species are responsible for a range of mucosal and cutaneous infections, which include oral candidiasis, esophagitis, gastrointestinal candidiasis, cutaneous candidiasis, and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Furthermore, Candida can lead to more critical systemic infections, with invasive bloodstream infections being the most prevalent and clinically significant among them (1).

Reports from numerous countries worldwide indicate an alteration in the epidemiology of Candida infections, marked by a gradual transition from the dominant species, C. albicans, to a prevalence of non-albicans Candida (NAC) species, including C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and Candida krusei (C. krusei) (2-5). Given that both pathogenicity and appropriate therapeutic approaches vary by species, accurate species identification is crucial (1). The recovery of these NAC organisms from diverse hospital settings and on the hands of healthcare personnel suggests nosocomial transmission. Noteworthy among these NAC species is Candida auris (C. auris), a recently recognized, multidrug-resistant yeast that has been responsible for outbreaks across several geographic regions. To implement stringent infection control measures within a hospital setting, rapid and accurate identification of C. auris is crucial (6).

The laboratory diagnosis of Candida is generally straightforward due to the microscopic presence of yeast forms and pseudo-hyphae. These organisms exhibit robust growth on standard culture media and in blood culture bottles, eliminating the need for specialized culturing ingredients. Conventional phenotypic assays, such as the rapid, presumptive germ tube test and chlamydospore formation, are employed to distinguish C. albicans from NAC species. However, these methods are incapable of providing further species-level differentiation among NAC isolates and are subject to inherent limitations of false positive and false negative results. Other phenotypic identification methods, which rely on biochemical reactions, include systems like the Analytical Profile Index (API), VITEK, and PHOENIX. However, these methods typically require 18-24 hours to yield identification results (1). Conversely, molecular approaches such as those based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing offer high accuracy but are often associated with significant processing time and considerable expense (7).

A novel approach employing matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) offers a rapid and highly accurate method for identifying yeasts directly from culture plates based on their unique protein profile, typically within 20 minutes (8,9). This technique was utilized in the current study, which was executed at a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, with the objective of identifying Candida species that were isolated from various clinical specimens through MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Methods

Study setting and design

This research, structured as a retrospective, laboratory-based study, utilized data procured from the Department of Microbiology at Father Muller Medical College Hospital in Mangalore, Karnataka, India, from September 2022 to November 2023. The study's cohort comprised all clinically significant Candida isolates that were successfully recovered from routine clinical specimens during the specified timeframe.

Specimen collection and processing

Blood samples were obtained and inoculated into BacT/ALERT aerobic culture bottles (bioMérieux, France). These bottles were subsequently incubated at a temperature of 37°C for a maximum duration of 5 days. Any bottles indicating a positive signal for yeast proliferation were subjected to Gram staining, followed by subculturing onto both blood agar and Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDA) media (Both supplied by HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India).

All remaining clinical samples, encompassing high vaginal swabs, urine, pus, central venous catheter (CVC) tips, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, nail clippings, ascitic fluid, wound swabs, tissue, bile, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), underwent processing in accordance with standard microbiological protocols. These specimens were inoculated onto suitable culture media and subsequently incubated at 37°C for 24–48 hours.

Specimens specifically requested for fungal culture were inoculated onto two separate slopes of SDA supplemented with gentamicin (Omitting cycloheximide). These cultures were then incubated at 25°C and 37°C for a maximum duration of four weeks. Direct examination of all specimens was conducted utilizing Gram stain and/or 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mounts for the primary purpose of detecting yeast cells.

Isolation and preliminary identification

Following an incubation period of 24–48 hours, culture plates exhibiting smooth, cream-to-white, and glabrous colonies-morphologically indicative of Candida species-were chosen for further analysis. A Gram stain was subsequently performed on these colonies to confirm the characteristic yeast morphology. These presumptive isolates were then subcultured onto HiChrome™ Candida Differential Agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) for a reliable, phenotypic differentiation based on colony color.

Species identification by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)

Species-level identification was definitively achieved utilizing the Bruker Microflex LT/SH MALDI-TOF MS system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in conjunction with MALDI Biotyper software (MBT Compass version 12.0.0.0_10833). This system operates by comparing the distinctive ribosomal protein spectra of the isolates against a specialized reference database for organism identification (10).

Sample preparation (Extended direct transfer method)

A pure colony was thinly smeared onto a polished steel MALDI target plate. Subsequently, 1 μL of a 70% formic acid solution was applied to the sample and permitted to air-dry at room temperature. Following this step, 1 μL of the α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) matrix solution was added and allowed to completely dry.

Data acquisition and interpretation

The MALDI Biotyper software was utilized in automatic mode to acquire the spectra. Interpretation of the resulting identification scores adhered to the manufacturer's established criteria: A score of ≥ 2.0 signified a high-confidence identification at the species level; scores ranging from 1.7 to 1.99 indicated genus-level identification with lower confidence; and scores of < 1.7 were classified as unreliable. The C. albicans ATCC 90028 functioned as the positive control, while spots containing matrix only were employed as the negative control (11).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data (Such as specimen type, species distribution, and demographic information) were presented using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables (e.g., patient age) were summarized by the median accompanied by the interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel were employed for data analysis.

Results

A comprehensive analysis was conducted on 342 Candida isolates derived from clinical specimens over a 15-month period, spanning from September 2022 to November 2023. The median age of patients at the time of infection was 46.5 years, with a notable male predominance. The primary source of the isolates was blood (136/342, 39.76%) (Table 1). NAC species constituted the majority (254/342, 72.84%), outnumbering C. albicans. Among the NAC group, C. tropicalis was the most prevalent isolate (30.40%), followed by C. parapsilosis (14.32%). Furthermore, 40 strains of C. auris were identified during the study (11.69%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Prompt and accurate identification of yeast is critical for effective patient management in any infectious process. Furthermore, the rising prevalence of NAC species can complicate the selection of appropriate antifungal therapy (3-6).

Infections caused by NAC species are clinically indistinguishable from those caused by C. albicans; however, antifungal resistance is more frequently associated with NAC species (1). Our current research demonstrated a predominance of NAC, accounting for 72.84% of the isolates responsible for various clinical candidiasis conditions. This finding aligns with a study conducted by Umamaheshwari et al. in Southern India, which reported that 73.64% of candidiasis cases were attributable to NAC species (5). Furthermore, the emergence and predominance of NAC in various body fluids have also been highlighted by Singh DP et al. (12).

In the current study, C. tropicalis (30.40%) was determined to be the most frequently isolated species. The finding of our study aligned with the results reported by Gautam et al. (26.72%) and Anita et al. (37.09%) for the isolation frequency of C. tropicalis (13,14). While traditional phenotypic identification methods, which rely on biochemical reactions, are cost-effective, they are inherently time-consuming. Conversely, techniques involving nucleic acid detection, although highly specific, are often expensive. Consequently, MALDI-TOF MS has emerged as a novel and efficient method for the identification and speciation of yeasts, such as Candida (9,11). MALDI-TOF MS was utilized for accurate species-level identification of Candida isolates. The on-plate extraction method simplified the procedure, and the technique demonstrated high throughput and cost-effectiveness. Specifically, its ability to analyze 96 isolates per run using inexpensive reagents makes it significantly more economical than traditional biochemical or nucleic acid-based methods. MALDI-TOF MS successfully identified all suspected Candida species. A high degree of confidence was achieved for 91.81% (314/342) of the isolates, with log scores > 1.7, which is consistent with findings reported by Periera et al. (10).

The multidrug-resistant yeast C. auris is frequently misidentified by conventional phenotypic automated systems as other Candida species, including Candida haemulonii (C. haemulonii), Candida famata (C. famata), Candida sake (C. sake), and Candida lusitanie (C. lusitaniae). Definitive confirmation of C. auris requires advanced methods, MALDI-TOF MS or DNA sequencing (15). In this study, a concerningly high prevalence of C. auris (11.69%) was observed, particularly among burn patients. These patients are highly susceptible to acquiring C. auris infections from the hospital environment due to their impaired immune defense and extensive wounds (16). This observed dominance of C. auris is consistent with findings from a previous study conducted in western India by Prayag PS (6).

Accurate and timely diagnosis of NAC is crucial for the selection of appropriate empirical antifungal treatment. Furthermore, the implementation of stringent infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols is essential for patients colonized or infected with C. auris to effectively contain this multidrug-resistant yeast and mitigate the risk of institutional outbreaks.

Conclusion

The role of Candida species, encompassing NAC and novel drug-resistant strains, necessitates a cautious approach in clinical and laboratory settings. MALDI-TOF MS offers a viable alternative to conventional and automated identification systems that rely on biochemical reactions for Candida speciation. Despite the significant initial capital investment, the use of less expensive reagents and the implementation of simplified protocols establish MALDI-TOF MS as a cost-effective method for the routine identification of yeast isolates from clinical specimens.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the faculty and technical staff of the Department of Microbiology for their valuable assistance.

Funding sources

This study did not receive any funding from public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Ethical statement

Reference No. FMIEC/CCM/550/2023 (Protocol No. 512/2023)

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author contributions

K.P.: Study concept, Study design, Data analysis, and Manuscript writing and Review; R.T.P.: Data collection and Manuscript writing; S.D. and B.A.: Data analysis and Manuscript review; M.D.: Manuscript review.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the corresponding author to any interested party upon presentation of a reasonable request.

Research Article: Original Paper |

Subject:

Mycology

Received: 2024/03/26 | Accepted: 2024/12/31 | Published: 2025/12/21 | ePublished: 2025/12/21

Received: 2024/03/26 | Accepted: 2024/12/31 | Published: 2025/12/21 | ePublished: 2025/12/21

References

1. Edwards JE Jr Candida species. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1985. p. 2289-306. [View at Publisher]

2. Meyahnwi D, Siraw BB, Reingold A. Epidemiologic features, clinical characteristics, and predictors of mortality in patients with candidemia in Alameda County, California; a 2017-2020 retrospective analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):843. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Ray A, K AA, Banerjee S, Chakrabarti A, Denning DW. Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in India. Open Forum Infect Dis .2022;9(12):ofac603. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Kaur H, Singh S, Rudramurthy SM, Ghosh AK, Jayashree M, Narayana Y, et al. Candidaemia in a tertiary care center of a developing country: Monitoring possible change in the spectrum of agents and antifungal susceptibility. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2020;38(1):110-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. S Umamaheshwari, Sumana MN. Retrospective analysis on distribution and antifungal susceptibility profile of Candida in clinical samples: a study from Southern India. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1160841. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Prayag PS, Patwardhan S, Panchakshari S, Rajhans PA, Prayag A. The Dominance of Candida auris: A Single-center Experience of 79 Episodes of Candidemia from Western India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26(5):560-3. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Eghtedar Nejad E, Ghasemi Nejad Almani P, Mohammadi MA, Salari S. Molecular identification of Candida isolates by Real-time PCR-high-resolution melting analysis and investigation of the genetic diversity of Candida species. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(10):e23444. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Maenchantrarath C, Nutalai D, Samosornsuk W, Sakoonwatanyoo P. Identification of yeasts from clinical samples using MALDI-TOF MS. Vajira Med J: Journal of Urban Medicine. 2020;64(4):297-310. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

9. Lau AF. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight for Fungal Identification. Clin Lab Med. 2021;41(2):267-83. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Pereira LC, Correia AF, da Silva ZDL, de Resende CN, Brandão F, Almeida RM, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis and current perspectives: new risk factors and laboratory diagnosis by using MALDI TOF for identifying species in primary infection and recurrence. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(8):1681-93. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for the identification of cultured microorganisms using Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. 1st ed. CLSI guidelines M58. Wayne PA: Clinical and laboratory institute 2017. Available from: https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m58/. [View at Publisher]

12. Singh DP, Kumar Verma R, Sarswat S, Saraswat S. Non-Candida albicans Candida species: virulence factors and species identification in India. Curr Med Mycol. 2021;7(2):8-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Gautam G, Rawat D, Kaur R, Nathani M. Candidemia: Changing dynamics from a tertiary care hospital in North India. Curr Med Mycol. 2022;8(1):20-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Anita, Kumar S, Pandya HB. Speciation and Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Candida isolated from Immunocompromised Patients of a Tertiary Care Centre in Gujarat, India. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2023;17(1):427-33. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

15. Keighley C, Garnham K, Harch SAJ, Robertson M, Chaw K, Teng JC, et al. Candida auris: Diagnostic Challenges and Emerging Opportunities for the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2021;15(3):116-26. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Moore R, Lie L, Pua H, Slade DH, Rangel S, Davila A, et al. 1225. The Perfect Storm: A Hardy and Lethal Pathogen and a Unit Filled with Immunocompromised Patients with Large Open Wounds. Troubles with Candida Auris in a Burn Intensive Care Unit. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(2):ofac492.1057. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

goums.ac.ir

goums.ac.ir yahoo.com

yahoo.com