Volume 19, Issue 6 (Nov-Dec 2025)

mljgoums 2025, 19(6): 12-15 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Subramaniam A, Raj S, Olakara T, S J K, Preetha Tilak V. Prevalence of cytogenetic and electrophoretic abnormalities in patients suspected of multiple myeloma. mljgoums 2025; 19 (6) :12-15

URL: http://mlj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1879-en.html

URL: http://mlj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1879-en.html

1- Department of Biochemistry, St. John’s Medical College and Hospital, Bangalore-560034, India

2- Department of Biochemistry, St. John’s Medical College, Sarjapur Road, Bengaluru 560034, India ,jayakumari.s@stjohns.in ORCID number: 0000-0002-2104-8228

3- Division of Molecular Biology and Genetics, St. John’s Medical College and Hospital, Bangalore-560034, India

2- Department of Biochemistry, St. John’s Medical College, Sarjapur Road, Bengaluru 560034, India ,

3- Division of Molecular Biology and Genetics, St. John’s Medical College and Hospital, Bangalore-560034, India

Full-Text [PDF 350 kb]

(264 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (762 Views)

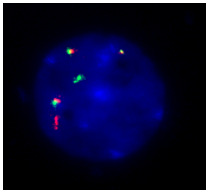

3. t (4;14) FGFR3/IGH DF: Orange-labelled probe binds to the FGFR3 gene region at 4p16.3, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3 (Figure 3).

6. TP53/NF1: Orange-labelled probe binds to the TP53 gene region at 17p13, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the NF1 gene region at 17q11.2.

7. t (6;14) CCND3/IGH DF: Orange-labelled probe binds to the CCND3 gene region at 6p21.1, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3.

8. t (14;20) IGH/MAFB DF: Green-labelled probe binds to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3, and an orange-labelled probe hybridizing proximal to the MAFB gene region at 20q12.

Data from confirmed MM cases and their FISH results were collected and analysed. Frequencies of cytogenetic abnormalities were calculated, and correlations between genetic findings and disease characteristics were assessed using chi-square tests.

Results

Eight hundred patients were evaluated for electrophoretic abnormalities. Out of these, 100 patients were diagnosed with MM, and 68 of these underwent FISH testing (Table 1).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a significant proportion (67.6%) of MM patients exhibit cytogenetic abnormalities detectable by FISH. The most prevalent abnormality, IGH break-apart, was found in 54.5% of cases. This abnormality is well-known for its association with MM and has been linked to unfavorable outcomes in multiple studies. The detection of TP53 deletion in 23.5% of cases also aligns with existing literature, as TP53 abnormalities often correlate with aggressive disease and reduced survival.

Translocations such as t (4;14) and t (14;20), while less common, were also detected in our cohort. These translocations have been implicated in high-risk disease and poorer response to conventional therapies. Monosomy 13 and monosomy 14, although infrequent, may contribute to disease progression and should be evaluated in larger studies. Several previous studies have reported similar patterns of genetic abnormalities in MM, although variations in the prevalence of specific abnormalities can be observed depending on the population and methodologies used. Our finding that IGH break-apart was present in 54.5% of cases is consistent with other studies, which typically report IGH rearrangements in 40 - 60% of MM patients. Rajkumar et al. found a prevalence of 50% for IGH abnormalities, which are known to be associated with poor prognosis and resistance to conventional therapy (2). Similarly, Fonseca et al. found that IGH translocations were the most common cytogenetic abnormality in MM, occurring in around 50% of cases, emphasizing its role in MM pathogenesis.

1. TP53 Deletion (23.5%): The prevalence of p53 deletion in our study (23.5%) is slightly higher compared to some studies, where the frequency typically ranges between 10 - 20% (14). According to Amudha et al., the translocations t (4;14), t (14;16), t (6;14), and t (14;20) showed an association with anemia. The t (4;14) abnormality, in particular, was linked to elevated serum monoclonal protein levels and increased plasma cell proliferation. In addition, monosomy 13 has been correlated with reduced survival and a tendency for progression from monoclonal gammopathy (15). Other studies, such as Abdallah et al., reported that TP53 deletions were detected in approximately 17% of MM patients and were strongly associated with advanced disease and poorer prognosis. This higher percentage in our cohort may reflect a referral bias of advanced or aggressive MM cases.

2. t (4;14) Translocation (14.7%): The t (4;14) translocation, detected in 14.7% of patients, is a well-established high-risk feature in MM. Reported frequencies for this abnormality in other studies range from 10 - 15%. Similarly, t (4;14) was reported in 15% of their cohort and noted that this translocation was associated with poor prognosis and a lower response to standard treatments (16). In contrast, Fonseca et al. reported a prevalence of around 13%, which further supports our findings.

3. t (14;20) Translocation (7.4%): Although t (14;20) is considered a rare genetic abnormality in MM, our study found a prevalence of 7.4%. This is in line with reported frequencies of 5 - 7% in previous studies. Patients with this translocation are often considered to have high-risk disease with shorter overall survival (14).

4. Monosomy 13 and 14: The detection of monosomy 13 (5.9%) and monosomy 14 (4.4%) in our study is consistent with other findings. Rajkumar et al. found that monosomy 13 occurs in about 15% of newly diagnosed MM patients and is associated with aggressive disease (2). However, our slightly lower detection rate may reflect differences in the specific populations being studied, or the fact that other genetic factors are now recognized as more predictive of outcomes in MM.

Amare et al. reported that FISH is a valuable and straightforward technique for detecting a wide range of cytogenetic abnormalities, providing important insights for disease risk stratification. They also noted that, when combined with mutational and gene-expression profiling in the future, FISH could contribute to more precise disease characterization and help identify actionable therapeutic targets (17).

This study highlights the importance of electrophoretic and genetic testing in the diagnosis and prognosis of MM. The prevalence of genetic abnormalities in MM patients, especially IGH break-apart, provides critical information about disease characteristics and expected outcomes. Further research is required to explore the therapeutic implications of these findings, particularly in the context of newer targeted therapies.

Conclusion

This study, along with previous research, emphasizes the critical importance of comprehensive cytogenetic profiling in MM patients. FISH analysis remains a valuable tool for identifying key genetic abnormalities that can influence prognosis and guide treatment decisions. Further studies exploring these abnormalities in different populations and their response to emerging therapies are necessary to refine prognostic models and optimize MM management strategies. The prevalence of IGH break-apart and TP53 deletions underscores their importance as biomarkers for disease aggressiveness and resistance to therapy. Translocations such as t (4;14) and t (14;20), though less common, highlight high-risk disease profiles that may benefit from early intervention with novel therapies. Molecular cytogenetic techniques, especially FISH, are indispensable tools in the evaluation of suspected multiple myeloma. They play a pivotal role in the detection of genetic abnormalities, guiding treatment strategies, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. The samples were analysed using probes that are limited to specific variations, and therefore, variations not covered by these probes cannot be detected. The ideal method for such cases would have been the use of mFISH and SKY. A future multicentric study on cytogenetics evaluation with electrophoresis on a larger population case with MGUS, SMM, and multiple MM is recommended.

Acknowledgement

We extend our gratitude to everyone whose contributions have been invaluable to this study.

Funding sources

It is not applicable.

Ethical statement

Institutional Ethics Committee approval for the study was obtained (IEC reference number 297/2022).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Amudha Subramaniam interpreted FISH laboratory reports. Saranya Raj contributed to the selection of laboratory and clinical data. Thashreefa Olakara reviewed medical records, collected and monitored data, interpreted results, maintained patient files and the master file, and drafted the final report. Jayakumari S. contributed to the concept and design, interpreted laboratory reports (Electrophoresis), monitored data, performed statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the final report. Veronica Preetha Tilak interpreted FISH laboratory reports.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a cancer involving plasma cells - specialized white blood cells that produce antibodies. The disease is defined by excessive, uncontrolled growth of a single clone of plasma cells within the bone marrow. This abnormal expansion results in increased production of monoclonal immunoglobulins or light chains, which can ultimately lead to damage in various organs. MM develops from a precursor condition known as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), which may progress to smoldering myeloma and eventually to symptomatic MM (1). It often presents with bone pain, anaemia, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction, but diagnosis requires specific laboratory evaluations (2). SPEP, IFE, and FLC analysis are the standard methods for MM diagnosis (3).

In addition, the identification of genetic abnormalities using FISH has provided valuable information about disease course and treatment response (4). Several key abnormalities are routinely studied because of their prognostic implications. These translocations, present in 10 - 20% of patients, influence prognosis, with t(4;14) associated with poor outcomes, while t(11;14) has a more neutral risk profile (5). Deletion of 17p (TP53), involving loss of the TP53 gene located on chromosome 17p, is a major high-risk abnormality and is strongly linked to more aggressive disease behavior and poorer patient survival. This abnormality occurs in 10 - 20% of cases and is a critical indicator of poor prognosis (6). Monosomy 13 or 13q deletion, involving deletion of chromosome 13 or loss of genetic material at 13q14, is seen in about 50% of MM patients.

Although historically considered a poor prognostic factor, its impact on outcomes has been overshadowed by other markers (7). Gain or amplification of CKS1B on 1q21 is observed in up to 40% of MM cases and is associated with worse outcomes, increased relapse rates, and shorter survival (8). Translocations t(14;20) and t(14;16) are rare abnormalities, observed in 1 - 2% and 5 - 10% of MM patients, respectively, and are considered high-risk features leading to poorer prognosis and shorter overall survival (9). These acquired cytogenetic abnormalities in MM samples are considered “known biomarkers” that assist in evaluating prognosis and determining therapeutic response. Owing to their importance in prognostic prediction and treatment planning, these cytogenetic abnormalities have been incorporated into risk stratification guidelines (10). Cytogenetic methods are essential for detecting chromosomal abnormalities, studying genome structure, and identifying genetic disorders and malignancies (11). FISH is a sensitive molecular cytogenetic technique used to detect chromosomal abnormalities with high resolution, even at the single-gene level (12).

Specific recommendations for performing FISH in myeloma by the European Myeloma Network aim to enhance understanding of myeloma pathogenesis and to provide standardized approaches using specific probes to establish common cytogenetic biomarkers for diagnostic work-up, thereby classifying the disease into subgroups with prognostic and predictive significance (13). Despite significant recent developments in the detection and treatment of MM, the disease remains highly heterogeneous, with variable clinical outcomes driven by genetic and molecular abnormalities. Understanding the genetic profile of MM is therefore critical for tailoring treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Although extensive research has identified several key cytogenetic abnormalities associated with MM prognosis, the prevalence and distribution of these abnormalities can vary across populations and geographic regions, and related data remain limited in the literature.

This study aims to evaluate the prevalence of electrophoretic and cytogenetic abnormalities in patients referred for serum protein electrophoresis in our population. Understanding these genetic abnormalities enables personalized treatment strategies, with high-risk patients benefiting from more aggressive therapeutic approaches.

Methods

This study is a retrospective study. All serum electrophoresis samples received between January 2017 and December 2023 in the Department of Biochemistry at St John’s Medical College were included. A total of 800 patients showing distortions, M-band, or spikes on SPEP were further evaluated using additional tests, including free light chain assays, immunofixation, and bone marrow studies.

Cytogenetic analysis was carried out at the Division of Human Genetics, St John’s Medical College, for patients confirmed with MM. FISH was performed on whole marrow samples to detect cytogenetic abnormalities specific to MM, using a comprehensive FISH panel of probes from Metasystems, Germany. These probes targeted various genes and chromosomal regions implicated in MM, such as the IGH break-apart probe on 14q32.3 and TP53 on 17p13.

FISH probes were applied on fixed cell suspension following a standardized FISH protocol, which included probe addition, co-denaturation at 75°C for 2 minutes, and hybridization at 37°C using Euroclone. This was followed by post-hybridization washes at 72°C, dehydration in an ethanol series, and DAPI addition. A total of 200 nuclei were analysed using a BX53F Olympus fluorescent microscope and digital imaging.

FISH probe specifications from XCyting FISH probes of metasystems

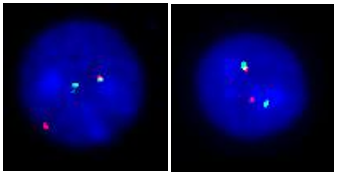

1. IGH BA: Orange-labelled probe partly binds to the constant region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the variable distal region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3 (Figure 1).

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a cancer involving plasma cells - specialized white blood cells that produce antibodies. The disease is defined by excessive, uncontrolled growth of a single clone of plasma cells within the bone marrow. This abnormal expansion results in increased production of monoclonal immunoglobulins or light chains, which can ultimately lead to damage in various organs. MM develops from a precursor condition known as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), which may progress to smoldering myeloma and eventually to symptomatic MM (1). It often presents with bone pain, anaemia, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction, but diagnosis requires specific laboratory evaluations (2). SPEP, IFE, and FLC analysis are the standard methods for MM diagnosis (3).

In addition, the identification of genetic abnormalities using FISH has provided valuable information about disease course and treatment response (4). Several key abnormalities are routinely studied because of their prognostic implications. These translocations, present in 10 - 20% of patients, influence prognosis, with t(4;14) associated with poor outcomes, while t(11;14) has a more neutral risk profile (5). Deletion of 17p (TP53), involving loss of the TP53 gene located on chromosome 17p, is a major high-risk abnormality and is strongly linked to more aggressive disease behavior and poorer patient survival. This abnormality occurs in 10 - 20% of cases and is a critical indicator of poor prognosis (6). Monosomy 13 or 13q deletion, involving deletion of chromosome 13 or loss of genetic material at 13q14, is seen in about 50% of MM patients.

Although historically considered a poor prognostic factor, its impact on outcomes has been overshadowed by other markers (7). Gain or amplification of CKS1B on 1q21 is observed in up to 40% of MM cases and is associated with worse outcomes, increased relapse rates, and shorter survival (8). Translocations t(14;20) and t(14;16) are rare abnormalities, observed in 1 - 2% and 5 - 10% of MM patients, respectively, and are considered high-risk features leading to poorer prognosis and shorter overall survival (9). These acquired cytogenetic abnormalities in MM samples are considered “known biomarkers” that assist in evaluating prognosis and determining therapeutic response. Owing to their importance in prognostic prediction and treatment planning, these cytogenetic abnormalities have been incorporated into risk stratification guidelines (10). Cytogenetic methods are essential for detecting chromosomal abnormalities, studying genome structure, and identifying genetic disorders and malignancies (11). FISH is a sensitive molecular cytogenetic technique used to detect chromosomal abnormalities with high resolution, even at the single-gene level (12).

Specific recommendations for performing FISH in myeloma by the European Myeloma Network aim to enhance understanding of myeloma pathogenesis and to provide standardized approaches using specific probes to establish common cytogenetic biomarkers for diagnostic work-up, thereby classifying the disease into subgroups with prognostic and predictive significance (13). Despite significant recent developments in the detection and treatment of MM, the disease remains highly heterogeneous, with variable clinical outcomes driven by genetic and molecular abnormalities. Understanding the genetic profile of MM is therefore critical for tailoring treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes. Although extensive research has identified several key cytogenetic abnormalities associated with MM prognosis, the prevalence and distribution of these abnormalities can vary across populations and geographic regions, and related data remain limited in the literature.

This study aims to evaluate the prevalence of electrophoretic and cytogenetic abnormalities in patients referred for serum protein electrophoresis in our population. Understanding these genetic abnormalities enables personalized treatment strategies, with high-risk patients benefiting from more aggressive therapeutic approaches.

Methods

This study is a retrospective study. All serum electrophoresis samples received between January 2017 and December 2023 in the Department of Biochemistry at St John’s Medical College were included. A total of 800 patients showing distortions, M-band, or spikes on SPEP were further evaluated using additional tests, including free light chain assays, immunofixation, and bone marrow studies.

Cytogenetic analysis was carried out at the Division of Human Genetics, St John’s Medical College, for patients confirmed with MM. FISH was performed on whole marrow samples to detect cytogenetic abnormalities specific to MM, using a comprehensive FISH panel of probes from Metasystems, Germany. These probes targeted various genes and chromosomal regions implicated in MM, such as the IGH break-apart probe on 14q32.3 and TP53 on 17p13.

FISH probes were applied on fixed cell suspension following a standardized FISH protocol, which included probe addition, co-denaturation at 75°C for 2 minutes, and hybridization at 37°C using Euroclone. This was followed by post-hybridization washes at 72°C, dehydration in an ethanol series, and DAPI addition. A total of 200 nuclei were analysed using a BX53F Olympus fluorescent microscope and digital imaging.

FISH probe specifications from XCyting FISH probes of metasystems

1. IGH BA: Orange-labelled probe partly binds to the constant region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the variable distal region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nuclei showing IGH break-apart on 14q32.3. Probe specifications: IGH BA consists of an orange-labelled probe partly covering the constant region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3 and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the variable distal region of the IGH locus at 14q32.3. |

3. t (4;14) FGFR3/IGH DF: Orange-labelled probe binds to the FGFR3 gene region at 4p16.3, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3 (Figure 3).

Figure 2. t (11;14) MYEOV/IGH DF is designed as a dual-fusion probe. The orange-labelled probe hybridizes to region 11q13 including CCND1, and the green-labelled probe flanks the IGH breakpoint region at 14q32.  Figure 3. Probe specification: t (4;14) FGFR3/IGH DF consists of an orange-labelled probe hybridizing to the FGFR3 gene region at 4p16.3 and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3. Nuclei showing extra fusion signals for t (4;14) translocation. |

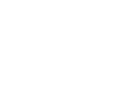

.PNG) Figure 4. t (14;16) IGH/MAF DF consists of a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3 and an orange-labelled probe hybridizing to the WWOX/MAF gene region at 16q23. Nuclei showing fusion signals for t (14;16) translocation. |

6. TP53/NF1: Orange-labelled probe binds to the TP53 gene region at 17p13, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the NF1 gene region at 17q11.2.

7. t (6;14) CCND3/IGH DF: Orange-labelled probe binds to the CCND3 gene region at 6p21.1, and a green-labelled probe hybridizing to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3.

8. t (14;20) IGH/MAFB DF: Green-labelled probe binds to the IGH gene region at 14q32.3, and an orange-labelled probe hybridizing proximal to the MAFB gene region at 20q12.

Data from confirmed MM cases and their FISH results were collected and analysed. Frequencies of cytogenetic abnormalities were calculated, and correlations between genetic findings and disease characteristics were assessed using chi-square tests.

Results

Eight hundred patients were evaluated for electrophoretic abnormalities. Out of these, 100 patients were diagnosed with MM, and 68 of these underwent FISH testing (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Distribution of electrophoretic and genetic findings

.PNG) |

|

Table 2. Prevalence of Genetic Abnormalities in MM

.PNG) |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a significant proportion (67.6%) of MM patients exhibit cytogenetic abnormalities detectable by FISH. The most prevalent abnormality, IGH break-apart, was found in 54.5% of cases. This abnormality is well-known for its association with MM and has been linked to unfavorable outcomes in multiple studies. The detection of TP53 deletion in 23.5% of cases also aligns with existing literature, as TP53 abnormalities often correlate with aggressive disease and reduced survival.

Translocations such as t (4;14) and t (14;20), while less common, were also detected in our cohort. These translocations have been implicated in high-risk disease and poorer response to conventional therapies. Monosomy 13 and monosomy 14, although infrequent, may contribute to disease progression and should be evaluated in larger studies. Several previous studies have reported similar patterns of genetic abnormalities in MM, although variations in the prevalence of specific abnormalities can be observed depending on the population and methodologies used. Our finding that IGH break-apart was present in 54.5% of cases is consistent with other studies, which typically report IGH rearrangements in 40 - 60% of MM patients. Rajkumar et al. found a prevalence of 50% for IGH abnormalities, which are known to be associated with poor prognosis and resistance to conventional therapy (2). Similarly, Fonseca et al. found that IGH translocations were the most common cytogenetic abnormality in MM, occurring in around 50% of cases, emphasizing its role in MM pathogenesis.

1. TP53 Deletion (23.5%): The prevalence of p53 deletion in our study (23.5%) is slightly higher compared to some studies, where the frequency typically ranges between 10 - 20% (14). According to Amudha et al., the translocations t (4;14), t (14;16), t (6;14), and t (14;20) showed an association with anemia. The t (4;14) abnormality, in particular, was linked to elevated serum monoclonal protein levels and increased plasma cell proliferation. In addition, monosomy 13 has been correlated with reduced survival and a tendency for progression from monoclonal gammopathy (15). Other studies, such as Abdallah et al., reported that TP53 deletions were detected in approximately 17% of MM patients and were strongly associated with advanced disease and poorer prognosis. This higher percentage in our cohort may reflect a referral bias of advanced or aggressive MM cases.

2. t (4;14) Translocation (14.7%): The t (4;14) translocation, detected in 14.7% of patients, is a well-established high-risk feature in MM. Reported frequencies for this abnormality in other studies range from 10 - 15%. Similarly, t (4;14) was reported in 15% of their cohort and noted that this translocation was associated with poor prognosis and a lower response to standard treatments (16). In contrast, Fonseca et al. reported a prevalence of around 13%, which further supports our findings.

3. t (14;20) Translocation (7.4%): Although t (14;20) is considered a rare genetic abnormality in MM, our study found a prevalence of 7.4%. This is in line with reported frequencies of 5 - 7% in previous studies. Patients with this translocation are often considered to have high-risk disease with shorter overall survival (14).

4. Monosomy 13 and 14: The detection of monosomy 13 (5.9%) and monosomy 14 (4.4%) in our study is consistent with other findings. Rajkumar et al. found that monosomy 13 occurs in about 15% of newly diagnosed MM patients and is associated with aggressive disease (2). However, our slightly lower detection rate may reflect differences in the specific populations being studied, or the fact that other genetic factors are now recognized as more predictive of outcomes in MM.

Amare et al. reported that FISH is a valuable and straightforward technique for detecting a wide range of cytogenetic abnormalities, providing important insights for disease risk stratification. They also noted that, when combined with mutational and gene-expression profiling in the future, FISH could contribute to more precise disease characterization and help identify actionable therapeutic targets (17).

This study highlights the importance of electrophoretic and genetic testing in the diagnosis and prognosis of MM. The prevalence of genetic abnormalities in MM patients, especially IGH break-apart, provides critical information about disease characteristics and expected outcomes. Further research is required to explore the therapeutic implications of these findings, particularly in the context of newer targeted therapies.

Conclusion

This study, along with previous research, emphasizes the critical importance of comprehensive cytogenetic profiling in MM patients. FISH analysis remains a valuable tool for identifying key genetic abnormalities that can influence prognosis and guide treatment decisions. Further studies exploring these abnormalities in different populations and their response to emerging therapies are necessary to refine prognostic models and optimize MM management strategies. The prevalence of IGH break-apart and TP53 deletions underscores their importance as biomarkers for disease aggressiveness and resistance to therapy. Translocations such as t (4;14) and t (14;20), though less common, highlight high-risk disease profiles that may benefit from early intervention with novel therapies. Molecular cytogenetic techniques, especially FISH, are indispensable tools in the evaluation of suspected multiple myeloma. They play a pivotal role in the detection of genetic abnormalities, guiding treatment strategies, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. The samples were analysed using probes that are limited to specific variations, and therefore, variations not covered by these probes cannot be detected. The ideal method for such cases would have been the use of mFISH and SKY. A future multicentric study on cytogenetics evaluation with electrophoresis on a larger population case with MGUS, SMM, and multiple MM is recommended.

Acknowledgement

We extend our gratitude to everyone whose contributions have been invaluable to this study.

Funding sources

It is not applicable.

Ethical statement

Institutional Ethics Committee approval for the study was obtained (IEC reference number 297/2022).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Amudha Subramaniam interpreted FISH laboratory reports. Saranya Raj contributed to the selection of laboratory and clinical data. Thashreefa Olakara reviewed medical records, collected and monitored data, interpreted results, maintained patient files and the master file, and drafted the final report. Jayakumari S. contributed to the concept and design, interpreted laboratory reports (Electrophoresis), monitored data, performed statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the final report. Veronica Preetha Tilak interpreted FISH laboratory reports.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Research Article: Research Article |

Subject:

Human Genetics

Received: 2024/11/4 | Accepted: 2025/08/27 | Published: 2025/12/24 | ePublished: 2025/12/24

Received: 2024/11/4 | Accepted: 2025/08/27 | Published: 2025/12/24 | ePublished: 2025/12/24

References

1. Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1046-60. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(1):101-19. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Willrich MA, Katzmann JA. Laboratory testing requirements for diagnosis and follow-up of multiple myeloma and related plasma cell dyscrasias. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(6):907-19. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Ratan ZA, Zaman SB, Mehta V, Haidere MF, Runa NJ, Akter N. Application of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique for detection of genetic Aberration in Medical Science. Cureus. 2017;9(6):e1325. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Puertas B, González-Calle V, Sobejano-Fuertes E, Escalante F, Rey-Bua B, Padilla I, et al. Multiple myeloma with t(11;14): impact of novel agents on outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):40. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Campo E, Cymbalista F, Ghia P, Jäger U, Pospisilova S, Rosenquist R, et al. TP53 aberrations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an overview of the clinical implications of improved diagnostics. Haematologica. 2018;103(12):1956-68. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Fonseca R, Oken MM, Harrington D, Bailey RJ, Van Wier SA, Henderson KJ, et al. Deletions of chromosome 13 in multiple myeloma identified by interphase FISH usually denote large deletions of the q arm or monosomy. Leukemia. 2001;15(6):981-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Hanamura I. Gain/amplification of chromosome arm 1q21 in multiple myeloma. Cancers. 2021;13(2):256. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Schavgoulidze A, Perrot A, Cazaubiel T, Leleu X, Montes L, Jacquet C, et al. Prognostic impact of t(14;16) in multiple myeloma according to the presence of additional genetic lesions. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:160. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Lu X, Andersen EF, Banerjee R, Eno CC, Gonzales PR, Kumar S, et al. Guidelines for the testing and reporting of cytogenetic results for risk stratification of multiple myeloma: a report of the Cancer Genomics Consortium Plasma Cell Neoplasm Working Group. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15(1):86. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Shakoori AR. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and its applications. In: Chromosome Structure and Aberrations. 2017. p. 343-67. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID]

12. Chester M, Leitch AR, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Review of the Application of Modern Cytogenetic Methods (FISH/GISH) to the Study of Reticulation (Polyploidy/Hybridisation). Genes. 2010;1(2):166-92. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Ross FM, Avet-Loiseau H, Ameye G, Gutiérrez NC, Liebisch P, O'Connor S, et al. Report from the European Myeloma Network on interphase FISH in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Haematologica. 2012;97(8):1272-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, Shaughnessy J, Gutierrez N, Stewart AK, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23(12):2210- 21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Amudha S, Drishya R, Veronica PT, Raina M, Mary MA. Cytogenetics of multiple myeloma. Indian J Genet Mol Res. 2023;12(2):55-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI]

16. Abdallah N, Rajkumar SV, Greipp P, Kapoor P, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma: association with disease characteristics and treatment response. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(8):82. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Amare PK, Khasnis SN, Hande P, Lele H, Wable N, Kaskar S, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma: Incidence, Prognostic Significance, and Geographic Heterogeneity in Indian and Western Populations. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2022;162(10):529-40. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

goums.ac.ir

goums.ac.ir yahoo.com

yahoo.com